23rd June 2022

A VISION FOR BYKER TOWN.

23rd June 2022

A VISION FOR BYKER TOWN.

Share

Shields Road, Newcastle, is widely held to be crap not just by Geordies but, if you believe the spurious “index” of high streets of which it came bottom in 2017 and 2019, the whole civilised world. Local opinion was split on what’s wrong, ranging from too many drunks roaming around the place to business rates being too high.

Anyone who thinks Shields Road is the worst high street in the country needs their head examining. Numerous locally listed buildings, homely cafes, useful specialist second-hand stores and two of the North East’s best bike shops are hardly characteristic of complete failure. But let’s play the game: high streets are complex and their struggles are not down to any single factor. And it’s plain that twelve years of austerity have made life beyond grim for a lot of the people for whom Shields Road is the nearest place to buy stuff. But there are high streets in poor areas that do OK – the West Road on the other side of the city centre, for instance – and some shamefully poor high streets in places where local income levels would suggest every other front should be a little boutique or deli but people prefer to drive to, say, Guildford.

Aerial View of Byker

What we see time and again, almost regardless of local demographics, is that high streets thrive when they serve a dense and mixed local population. The clue’s in the name: the high street is, or should be, the place in the neighbourhood where people living and working locally gravitate to have their everyday, and perhaps less everyday, needs and wants met. Typically, a good high street will have things that grease the wheels of life – the café, the bakery, the pubs, the hairdressers, the phone repair place, at least two branches of Greggs… ; ) – and some things people might come from further afield for – those bike shops; a place to buy fishing tackle or outdoor gear; a niche clothes shop, perhaps. Maybe even a church or a school, those reliable generators of footfall back when people walked (or went) to them.

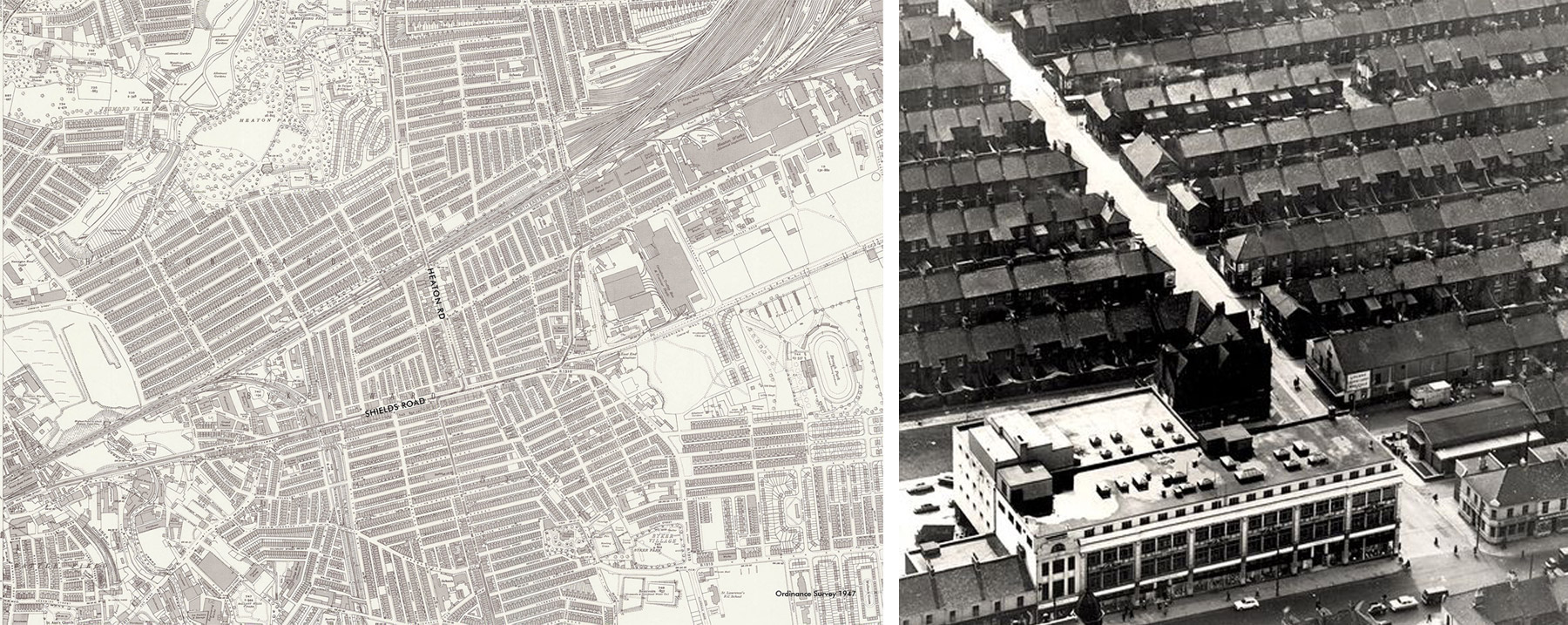

Two things happened to Shields Road to hobble its high street function. First, old Byker was pretty much cleared between the railway to the north and the river Tyne to the south. Dense terraces, generally running north-south and acting as tributaries of people into the east-west flow of local movement along Shield Road were replaced by looser, less legible developments of mostly social housing. To the south this manifested in the wondrous Byker Estate; to the north a messier tangle of smaller schemes. This is not a lament for the often slum-like Victorian housing of the past, or a call to demolish more perfectly good postwar housing; but it’s a simple fact that Shields Road just has many fewer chimney pots around it than it used to, so fewer people able to spend what money they have on it; which of course leads to a shrinking of choice, and so the vicious circle closes. And, urbanistically, Shields Road and the southern end of Heaton Road now sit as almost vestigial reminders of the power of the connective street grid while the wider neighbourhood around them often dissipates, obstructs and confuses.

1947 Street Pattern and Aerial Image Showing Terraces off Shields Road © Newcastle Libraries

Second, though, just to finish the place off, someone thought it was a good idea to drive a sunken bypass around Shields Road to the south. Even allowing for good intentions and the spirit of the age, it is hard to overstate how disastrous a decision this was. Literally a kilometre-long canyon separating the Byker Estate from its own town centre, with a few well-placed but windily hostile pedestrian overbridges, it is (in a crowded field) possibly the most useless piece of fast-road ‘infrastructure’ ever built in Newcastle and certainly the one that has done the most to trash the local in pursuit of faster global movement. Barely useful as a traffic sewer, it nonetheless effectively starves Shields Road of the passing trade that traditionally supplemented the local population in sustaining high-street trade.

Existing Site Plan

The contemporary product of this piece of trafficism is a vast shatter zone between the bypass and Shields Road itself which is surely one the most forlorn and depressing non-places anywhere in Tyneside. Car parks, big-box bingo halls and a most peculiarly sited leisure centre exist in a tangle behind the stumps of the old streets off Shields Road. Having run the gauntlet of the winds across the bypass, this illegible mess is what Byker Estate residents have to navigate if they want to get to the high street. Why would you, unless you really had no choice?

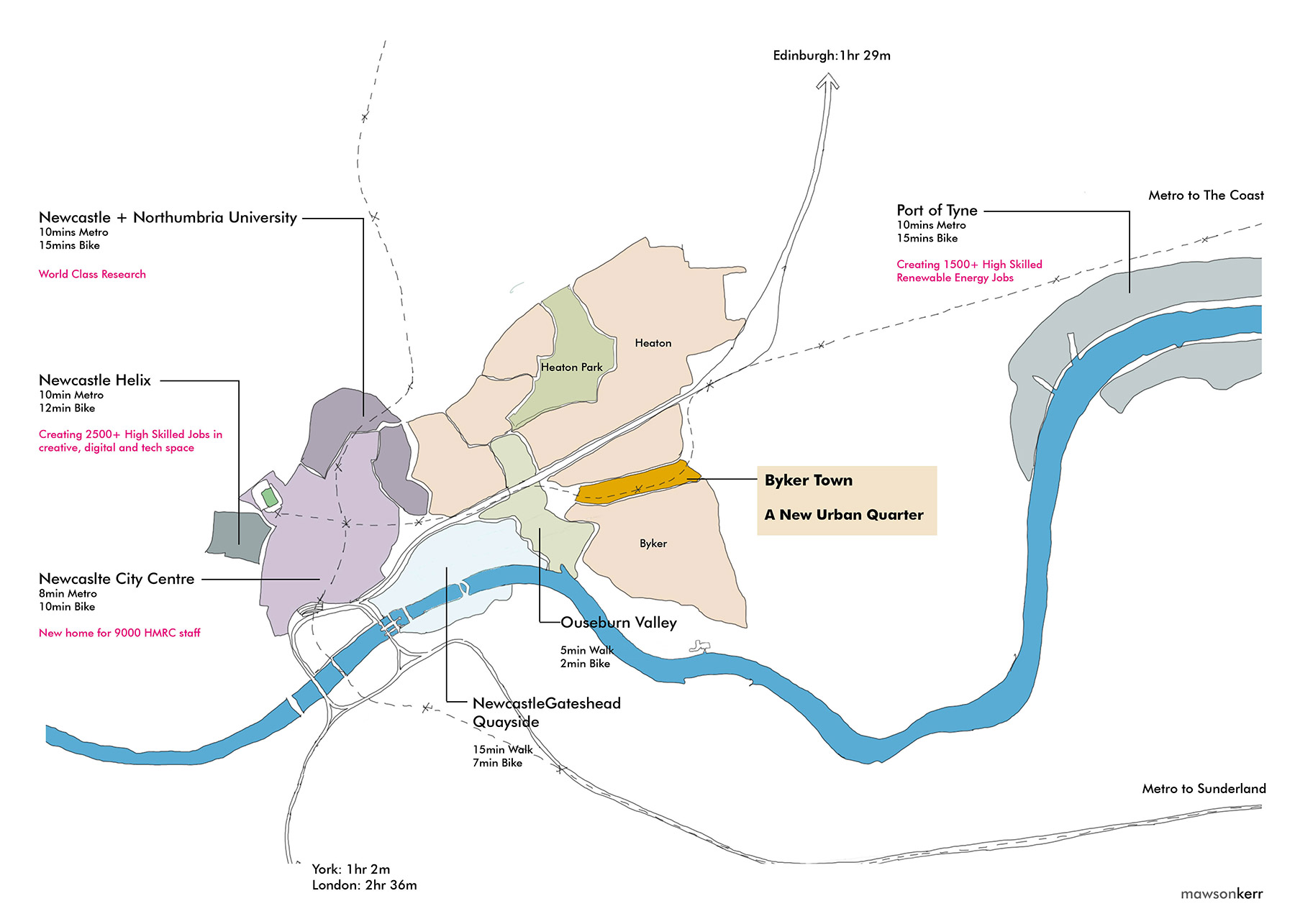

Amid the chaos, however, it is hard to ignore the sweeping grandness of the location. The Byker Wall, disliked as a piece of townscape mainly by those who do not understand solar orientation or climatic design, stretches away towards the prospect of the city in the distance, foregrounded by the Ouseburn valley, Byker bridge and the magnificent Metro viaduct. In a city of great topographical drama, it is one of the very best views and it’s not difficult to imagine when Shields Road was the bustling, tram-lined eastern approach to Newcastle or that it might be so again. Viewed through a lens not of current malaise but future possibility, this is an area of hugely underdeveloped urban land with a Metro station bang in the middle and a just-add-people high street ready to thrive – and, in doing so, perhaps reduce a little the pressure to build ever more nonplace car-dependent ‘aspirational’ housing on the city’s outskirts.

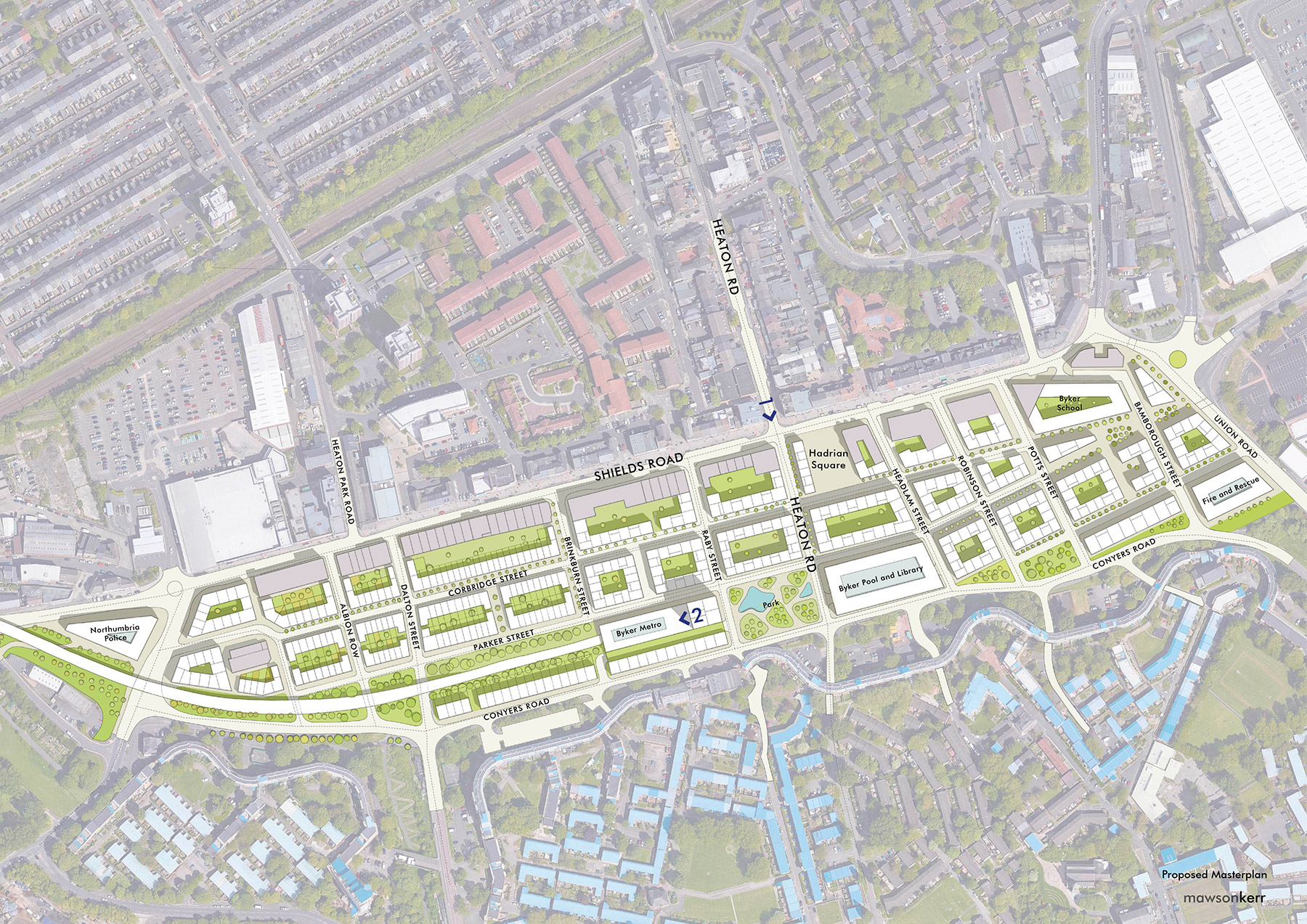

Proposed Site Plan © Mawson Kerr

Daniel Dyer’s proposal for Byker Town taps this potential. His plan would see the Shields Road bypass filled in and the no man’s land between Shields Road and Conyers Road redeveloped as a compact, walkable neighbourhood built around a reinstated grid of streets tying into the stumps of the old side streets off Shields Road and the existing routes into the Byker Estate. This dense, permeable urban network will naturally feed local movement onto Shields Road, which would be remodelled to provide direct segregated cycle paths into the city centre, a narrower carriageway which would allow cars and buses at low speeds as guests, and much-improved landscape. The only surgery proposed to Shields Road itself is to punch a new street through southwards as a continuation of Heaton Road, creating a stronger north-south axis giving access to a new Hadrian Square and a new park next to the Metro station and relocated Byker pool and library.

Byker Town with the continuation of Heaton Road © Mawson Kerr

Daniel’s plan envisages around 1,200 new homes, mostly in courtyard blocks of apartments and duplexes, with some family terraced housing at the western end. Generally at 4-6 storeys – a scale at or below that of the Wall – the highest densities are at the places of highest public transport accessibility – i.e. next to Byker Metro station – and next to the station itself there is an opportunity for a higher block, conversant with the scale of Tom Collins House – Byker’s tallest building – overlooking the new park.

Byker and the wider city from the Byker Metro Tower © Mawson Kerr

Homes would almost everywhere be dual aspect and have access to private or shared courtyard garden space, with balconies to maximise the extraordinary views and roof spaces given over to a photovoltaic microgrid that would generate a good portion of the development’s energy needs. The grid layout would erase the tangle of dead ends, blank facades and ungoverned spaces that currently make parts of the area feel dangerous, putting eyes on each street.

The plan reprovides for all of the atomised uses currently sitting in the backlands – fast-food places, bingo halls – within street-facing ground-floor spaces with residential above close to the Metro station and new Heaton Road – time and again the proven way to accommodate a thriving mix of uses in an urban neighbourhood. Police and fire and rescue stations are provided at the bookends of the plan close to the wider road network. Of course, the mix of uses would evolve and diversify as an expanded Byker of perhaps 3,500 more people took shape: less drive-thru, more walk-to.

The project is envisaged to be largely car-free, because the location affords great accessibility and excellent alternative modes of travel – and because why would you build the progressive city of the future around the individualist technology of the past? And why would you kneecap a scheme motivated principally by the desire to reinvigorate a local high street with the means to damage it further? What little car parking there would be, much of which would be for visitors to public services and essential users, could be contained in a retained underground section of the bypass, allowing for most of the surface streets to be access only and thus become lively spaces for socialising and play.

What of the economics of this venture? It might, still, be too much to ask that the merits of such bold ideas as Daniel’s be evaluated against sustainable whole-life economic models such as the Doughnut; in which case, no, it won’t ‘pay for itself’. Byker is not a wealthy place; land and property values are low. A thought-experiment might see the Byker Estate thrown to the market, in which case it would surely and rapidly become Newcastle’s Barbican – full of gentrifiers whose money changes the place for the better, and also for the worse, with investment following it in. That won’t and shouldn’t happen, but from a policy point of view you can’t keep a place poor and then complain that something that might radically improve conditions for people living there requires subsidy. So, yes, it will need public money – maybe the kind of scale of public money that was made available in the tens of millions of pounds (at today’s rates) to plough a bypass through the neighbourhood in the 1970s and is still available in the hundreds of millions for urban roadbuilding in 2022.

Which bring us to the road – the Shield Road bypass. In talking this concept through with friend and contacts, including council officers, we returned often to the same questions: what are you going to do with traffic? Where is it going to go? There isn’t space here to crunch numbers, debate induced demand and its reverse, or discuss how and why the answer to traffic needs just to be less of it and how we achieve that. But let’s consider this: the Metro is dying, and it is dying not because central government won’t dispense enough grant but because the same politicians who always say you can’t restrict cars without providing “alternatives” have declined for 40 years to plan Newcastle and its hinterland sustainably around an asset that is the envy of many cities across the UK and beyond.

Let’s imagine momentarily that, rather than beggar-thy-neighbour Britain, we’re in Sweden or Netherlands or France where, when you build a piece of urban infrastructure as iconic and useful and downright expensive as the Metro, you use every lever you have to build your compact city around it and measure the benefits not just in money but in social and environmental cohesion; and over decades not years. Through this lens, Byker deadzone is not a ‘challenge’ but a vast unrealised opportunity – to build the compact liveable city, to sustain one of Britain’s best pieces of urban infrastructure and to give many more Newcastle people present and future a piece of their city’s heartland.