1st December 2022

CO-LIVING IS AN EXPERIMENT ON VULNERABLE PEOPLE AT SCALE.

1st December 2022

CO-LIVING IS AN EXPERIMENT ON VULNERABLE PEOPLE AT SCALE.

Share

In an article in The Developer, TOWN director Jonny Anstead asks whether it’s right to deploy an untested model of housing without robust evidence of the potential positive and negative impacts. Read the full article below.

If you’re not already familiar with the concept of co-living, you soon will be. Although a nascent sector, it’s one that’s seeing rapid expansion. A mix of established developers – mostly those already well-versed in the world of purpose-build student accommodation – and new players are increasingly active in the market, supported by a wall of capital desperate for deployment into a movement that is on the rise, leaving investment agents salivating.

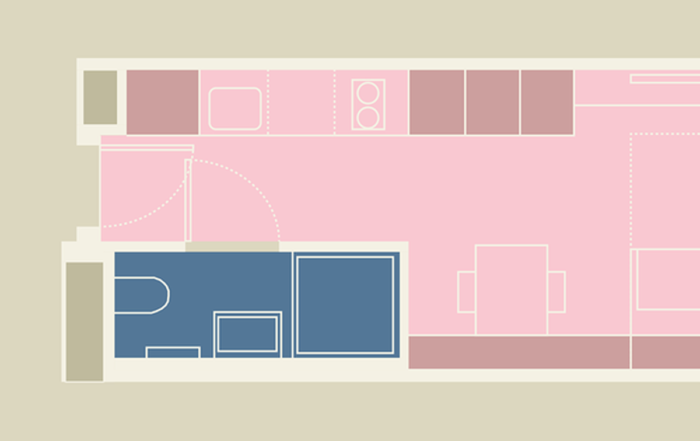

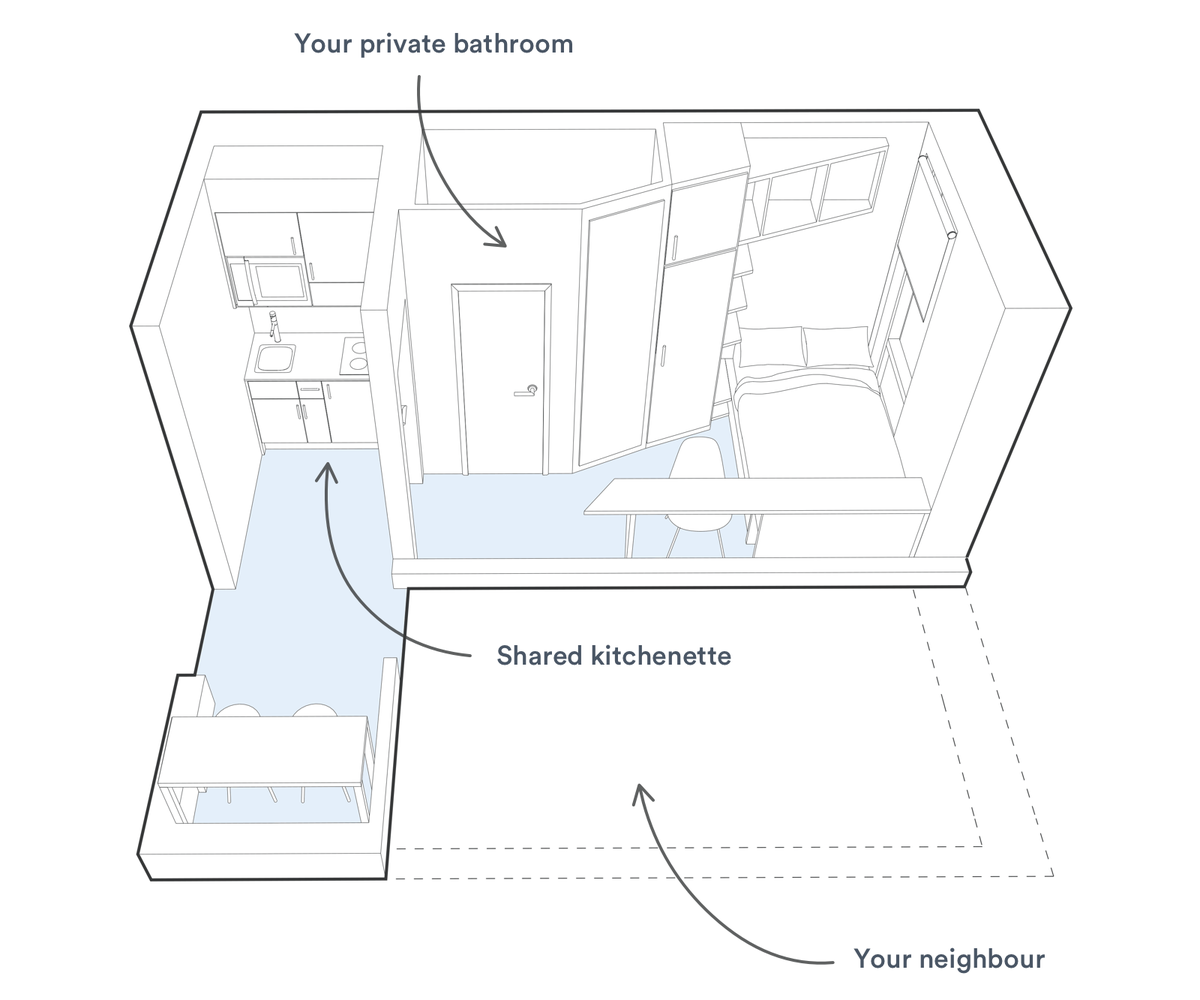

The co-living offer is simple: a private studio, typically around 20-25m2 in size, consisting of an open-plan bedroom with kitchenette as well as a private bathroom. Make no mistake, this is closer in size to a hotel room than an apartment, and well below the minimum floor area required for a self-contained studio, which is 37m2. Alongside the private room, however, residents have access to a range of shared facilities. These vary from scheme to scheme but may include high-end kitchens, dining spaces, yoga rooms, cinemas, gyms and co-working spaces. Rooms are available on a rental basis, inclusive of bills, and with varying degrees of flexibility, offering customers the ability to rent for shorter or longer periods as required.

For policymakers, there is an attraction to the co-living model. In the face of the housing crisis – whose effects on leading international cities are most pronounced – it is almost inevitable that there will be a downward pressure on living space, however fierce the defence of minimum standards. A solution that promises to deliver a lot of homes quickly and in a way that offers real benefits to the people who live in them is bound to excite plan-makers. The London Plan has already accepted that co-living will play a role in its future housing mix, allowing for “large-scale purpose-built shared living developments” in well-connected locations.

The inside of an apartment at The Collective as photographed by a guest.

The kitchenette is shared with a second studio flat. Both photos by Simon Gunton/Google Maps.

But it’s a product that comes with a hefty price tag: £1,300-2,000 per calendar month. While there is indisputable merit in the simplicity of an inclusive package that includes all bills, it’s pretty clear that co-living is a premium product aimed at young professionals: Graduates, familiar with the inherent sociability and space limitations of student life, taking their first steps into a new career or city, underwritten by the bank of mum and dad, and faced with a limited rental market. It’s little wonder that the prospect of a simple, ready-made package of home and amenities makes for an attractive proposition.

Beyond convenience, co-living sells the dream of community. The Collective, one of the largest operators in the sector, whose Old Oak development of 500 homes is the best known co-living development in the UK, states that its aim is to “foster human connection and enable people to lead more fulfilling lives”.

While some point to the benefits of reduced isolation and improved wellbeing, others indicate the health risks and negative impact of a life lived in the confines of a tiny space.

The smallest unit at The Collective Old Oak, the “twodio”, starts at £1,359 per calendar month. On Facebook and other review sites, there are frequent complaints about the size of the rooms, the tiny bathroom and overheating or freezing temperatures, but also some positive mentions of their events making it easy to meet other people. Several comments suggest the flats are being used as a short-stay hotel.

More-recently established developer Folk, promises to help its customers “make new friends and lifelong memories with them”. It’s a compelling idea, even if the imagery that underpins it – photogenic twenty-somethings chatting on designer sofas and sharing food at industrial tables – falls readily into cliché.

The “twodio” flat at The Collective starts at £1,359pcm and features a shared kitchenette with another unit.

But whether the co-living product lives up to this promise of friendship and connection is a matter for debate. While some point to the benefits of reduced isolation and improved wellbeing, others indicate the health risks and negative impact of a life lived in the confines of a tiny space. Julia Park, head of housing research with Levitt Bernstein, has raised the risk of negative impacts on mental health, while Tom Copley, deputy mayor of London for housing, has described the abandonment of minimum space standards as a race to the bottom.

There are also concerns about safety. In the paper, “I felt trapped”: Young Women’s Experiences Of Shared Housing In Austerity Britain, published in the journal Social & Cultural Geography, authors Iliana Ortega-Alcázar and Eleanor Wilkinson point out that while sharing may be positive when freely chosen, those forced to share for financial reasons can have negative experiences. Based on interviews with 40 women living in shared accommodation with strangers, the paper reveals some women are living in a position of heightened vulnerability and view their home as “a place of insecurity and fear”.

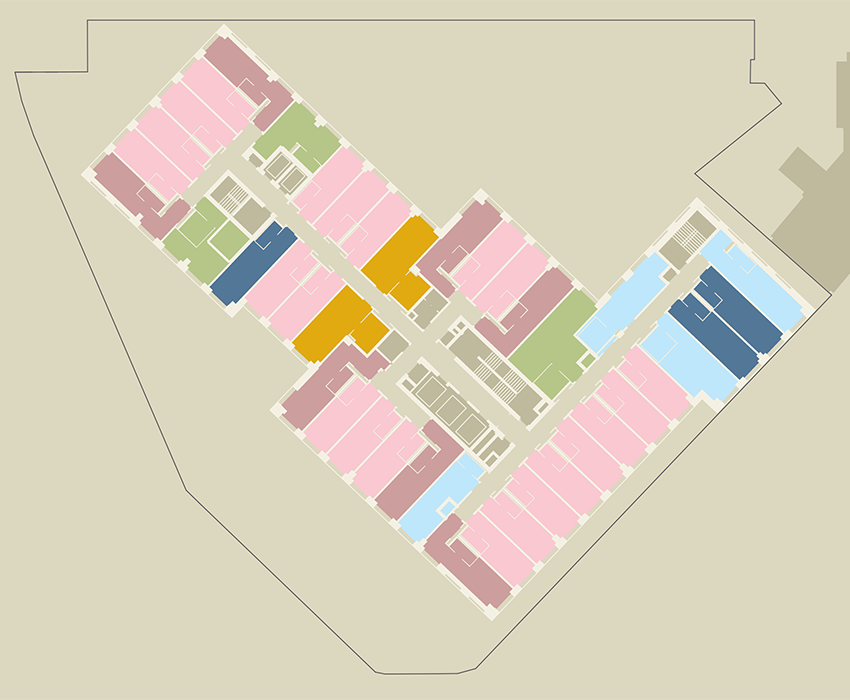

Proposed layout of the Greystar co-living scheme of 547 flats, designed by Hawkins\Brown and rejected by Wandsworth Council.

In September, Wandsworth councillors voted to turn down a co-living application of 547 studios, designed Hawkins\Brown for developer Greystar, despite the planners having recommended it for approval. Conservative Councillor Mark Justin said, “I don’t like the idea that Battersea is going to be an experiment for this kind of high-density tower block living.”

And this – the fact that it is an experiment – is much of the issue. There is little, if any, serious post-occupancy research designed to understand the impact of co-living on the wellbeing of people living in small units with shared amenities. To be taken seriously in the future by policymakers and the public, the sector needs to do a lot more to substantiate the benefits and head off concerns, through the rigorous evaluation of the quality of life of those living in such developments. Is it right to deploy a largely untested way of living on potentially vulnerable people at scale, without robust evidence of the positive and negative impacts?

What seems clear to me is that, in spite of the communal image it portrays, co-living offers a highly transactional and commoditised product, whose growth will owe more to the failure of the wider housing market than to its inherent merits. It should certainly not be confused with co-housing or community-led housing, which shift the balance of power towards residents, through collaboration, co-design and management approaches that put residents in genuine control.