13th March 2023

THE 15-MINUTE CITY IS SOMETHING WORTH FIGHTING FOR.

13th March 2023

THE 15-MINUTE CITY IS SOMETHING WORTH FIGHTING FOR.

Share

“In the face of bizarre conspiracy theories, those of us who argue for walkable neighbourhoods will have to up our game and explain ourselves better” writes TOWN Director Jonny Anstead in the Architects’ Journal. Read the full article below.

Architects and town planners across the country find themselves at the unlikely centre of a new front in the culture wars: the 15-minute city. It is based on seemingly the most harmless of planning concepts – the idea that cities should be designed to provide shops, schools and other daily amenities within a 15-minute walk of home. It is an idea advanced by academic Carlos Moreno and has been applied in cities throughout the world. Paris mayor Anne Hidalgo adopted the concept for her 2020 re-election campaign – and more recently the C40 global network of nearly 100 city mayors taking action to combat climate change, chaired by London mayor Sadiq Khan, followed suit.

Now, it appears, a co-ordinated campaign of disinformation has been launched to discredit the concept, portraying it as a sinister attempt by the state to control people’s general freedom of movement and even to confine individuals to their neighbourhoods.

Protestors marching against ’15-minute city’ plans in Oxford, February 2023.

While it’s easy to take aim at the more outlandish conspiracy theories, it’s important to recognise they hold an element of truth. While the 15-minute city is fundamentally about meeting daily needs within a walk of home, intrinsic to this approach is the principle of prioritising the movement of pedestrians and cyclists over car users. As such, the 15-minute city is closely allied to that other measure that seeks to restrict car use – the low-traffic neighbourhood (LTN). Aiming to create safer, more pleasant neighbourhood by limiting vehicle movements on domestic streets, LTNs have met furious responses in all quarters of the country.

“We shouldn’t be surprised at the depth of feeling against any measure perceived to seek to limit car use.”

Maybe we shouldn’t be surprised at the depth of feeling – however misjudged we feel it to be – against any measure perceived to seek to limit car use. Nearly a century of woeful land-use planning – supported by highly effective automotive advertising – has forcefully connected quality of life with the freedom to drive. And, given the lived reality of the many who live in sprawling, low-density suburbs with neither character not amenity, is it any wonder that the notion of a dense, walkable neighbourhood complete with schools, shops and doctor’s surgery seems, at best, a pipedream? At its heart, the clash concerns competing ideas of personal freedom. The 15-minute city promises greater freedom and control, by enabling people to live a rich, diverse life of their choosing, within a walk or cycle of home. In doing so, it challenges another freedom: the freedom to drive without restraint. Addressing this conflict requires evidence, including robust, post-occupancy research, to demonstrate the overall benefit to people’s quality of life, and show that the positives outweigh the negatives.

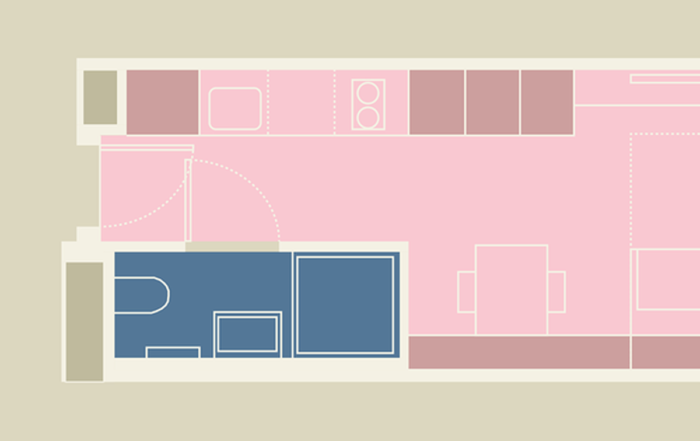

Moreover, the 15-minute city needs to tackle the thorny issue of the suburbs. It is one thing to apply 15-minute principles to city centres and planned new settlements – but how does existing, suburban Britain fit into this vision? This needs innovation – in terms of how we retrofit mixed uses to established, mono-use neighbourhoods – and new ways of working, not least from the housebuilders that tend to deliver them. Without these, 15-minute cities will, sadly, risk remaining the reserve of the metropolitan elite.

For those of us who have used the 15-minute city to frame our projects – and I am one – our work has become much harder. We can no longer rely on the catchphrase – as neat as it is – to do our work for us. We will have to work all the harder to articulate our ideas, marshal the evidence, engage people in the conversation and build consensus. Ultimately, maybe that is a good thing.